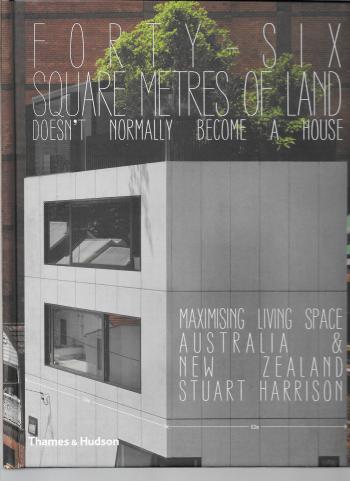

Title: Forty-Six Square Metres of Land Doesn’t Normally Become a House

Author/s: Stuart Harrison

Photographer/s: Baker, Andy; Bennetts, Peter; Boardman, Brett; Browell, Anthony; Burrows, Scott; Cadenhead, Paul; Cross, Emma; Devitt, Simon; Dwyer, Matthew; Finn, Brendan; Frith, Robert; Frederick Jones, Christopher; Fredericks, Murray; Gollings, John; Griffith, Tim; Hyatt, Peter; Linkins, John; Lu, Katherine; McCredie, Paul; McGrath, Shannon; Mein, Trevor; Newton, Matthew; Noble, Florence; Noonan, Sam; Peachey, Hugh; Power, Richard; Reynolds, Patrick; Rodriguez, Patrick; Scowan, Mark; Stout, Julie; Swawell, Derek; Wallace, Neil; Wong, Bo; Wuttke, Andrew; Young, Rohan.

Editor: Jane Angus (Writers Reign)

Design: Chase & Galley

ISBN: 978-0-500-50029-3

Size: 221mm by 289mm, 279p.

Publisher: Thames & Hudson

Publisher www: http://www.thameshudson.com.au/

When you pick up a book, particularly one on architecture, you expect to see a certain layout. There will be an introduction and contents page, followed by slabs of text with accompanying illustrations and photographs, concluding with an index or list of architects and/or photographers. This is the standard template of a book and it is unusual to find something that does not conform to this. Forty-Six Square Metres of Land Doesn’t Normally Become a House is that exception.

Examining examples of houses from Australia and New Zealand that occupy restrictive urban spaces, the book embodies the same mind-set as that of the designers of these small houses. The inside of the front cover, normally an empty space with no content, is here the beginning of the first case study. The inside of the back cover is the end of the last case study. Absolutely no space is wasted in this book; not a single page is empty and the design de-emphasises negative space. The title page, contents and indexes are sandwiched in the centre of Forty-Six Square Metres, distinguished from the surrounding white pages by being printed on a soft red that jumps out as you leaf through. This design choice still allows the book to be easily navigated, but is a fresh approach to how books can be read, which is a perfect parallel to the content.

The case studies in this book are focused on inventive solutions to compact building locations. The buildings are arranged from the smaller structures on smaller pockets of land (46m2) up to larger blocks containing apartments or collections of terrace houses. While the block sizes for these later case studies can be quite large (up to 1150m2), their designs have similar goals to those of the earlier houses, with maximising the density of habitation being at the forefront. To best show how the architects are responding to these goals, Forty-Six Square Metres includes a small graphic with each case study that shows key statistics, including the site area and the number of dwellings/inhabitants for the block. These graphics are easily understood and compared across the included houses, and their design is small enough to fit into the margins of the page, further paralleling the design principles of the architects.

The houses in Forty-Six Square Metres are not in stunning natural surrounds and don’t have the luxury of large spaces—as has been said, they have been built on small urban blocks—but that does not mean that they are not stunningly and lovingly designed. Utilising multiple floors, each house can increase its liveable space and gain a view over the surrounding area, and there is a large emphasis on outdoor space and vegetation as an important part of any house.

The first and smallest-by-footprint house, Small House (2), has a five-story height with the top floor being a green escape from the urban surrounds, including a vegetable garden and lemon tree in pots. The Skylight House (70) uses natural light to brighten the typically dark central section of a terrace house into an indoor courtyard, complete with a growing tree. A similar tree, this time enlivening a library space, is to be found within the Raven House (192). Though space is limited in every one of the featured houses, gardens and trees are prioritised to bring life and greenery into these urban dwellings.

Surrounded by the city as these houses are, you would expect each of them to be mostly built of steel, brick and concrete, and while these do play large roles in many of the houses, wood is just as frequently a major feature. Some of the houses leap out of their urban surrounds through their use of wood, such as the Stirling House (52), whose exterior is defined by wide grey bark planks, or the Ormond Esplanade (172), which has unusual vertical plank cladding along a curving façade.

Where the exterior are often colder steel and concrete, the interiors typically use wood to bring warmth into living spaces and bedrooms. The Tube House (84) is outside very modern with clean colours and sleek lines, but within rich hoop pine defines its sun-brightened top floor. House Shmukler (148) similarly uses plywood to envelope interior boxes, creating homely spaces, and the O’Sullivan House (220) uses wood to even more strongly enliven the central spaces of this light-filled family home. The limits of space that have been imposed on each of these houses have not prevented the architects from creating warm spaces that do not ignore sustainable design practices.

City spaces for living provide many benefits but are at the mercy of available space, with increasing urbanisation squeezing that space tighter and tighter. The houses in Forty-Six Square Metres respond to this issue in creative and responsible ways, bringing life and joy back into the sometimes-bleak inner city. This book provides an approach into the modern ways in which architects are recreating the house for a modern context and is a brilliantly designed and written piece.