Visual grading is the traditional method of determining a stress grade. It is still used for many structural products in Australia including most seasoned and unseasoned hardwoods, and unseasoned and thicker seasoned softwoods. It is also commonly used overseas including Europe and North America.

In a visual grading process, a trained grader examines each and every piece of timber produced. This visual inspection is undertaken in accordance with either the hardwood or softwood visual grading standards, which define rules as to the types sizes and positions of physical characteristics that are allowed into each 'group' or structural grade of material. The size and position of knots and other potential strength reducing characteristics in each piece is compared with the size and position of these characteristics allowed in the various grading classifications. The highest grades allow fewer and smaller characteristics in each piece of timber.

In general, visually stress-graded structural timber is sold in Australia by F-grade, rather than by Structural Grade Number. Most Australian native and imported structural hardwoods are graded using visual grading techniques. Some softwoods that are thicker than 45 mm are also visually graded. Most imported softwood is visually graded to the Australian grade rules.

Visual grading rules for strength are quite different to the visual grading rules for appearance, not only in the severity of the characteristics that are allowed, but also in the ones that are important.

The grading process is reliant on the skill of the graders, with visual grading rules quite complex - there are over 20 different characteristics that need to be checked.

The work is very demanding and often has to be accomplished at reasonably high speed. It requires the grader to examine each board on all surfaces before physically placing it in a stack corresponding to Structural Grade 1 through to Structural Grade 5. The highest strength properties are expected from material sorted into Structural Grade 1.

The Australian softwood visual grading rules are quite complex and define a number of different stress grades. The rules are applied to the timber at the end of the production line, after green sawing, drying, planing and docking (the operators of the docking saw are trained graders who remove features that would reduce the grade of full length pieces).

The grading rules have provisions for strength limiting characteristics and also for utility limiting characteristics. The following are examples of the type of characteristic that must be checked:

Strength limiting characteristics

In softwoods, pith is the dark spot that was the upward growing twig when the tree was very young. It signifies the presence of 'core wood' or 'juvenile wood'. Where the density of the wood is low, this can reduce the strength of the timber. In grading of softwoods, the visual grader has to estimate the spacing of the annual rings to determine whether or not a piece with core wood is within the specification of this grade.

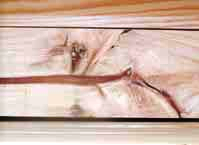

Surface checks are shallow cracks on the surface, mainly from the release of residual stresses on drying. The grader must check all cracks to see that they are not a split (that runs from one face to the other), and if a check (shallow crack) that they are not too wide, or too long.

Depending on the location of the knots, different limits apply. They are estimated by the Knot Area Ratio (KAR) which requires a grader to visualise the knots going right through the cross-section. The KAR is the percentage of the cross-section that is taken up with knots. Different limits on KAR apply for knots in the margin (outer quarter of the wide face) and for the centre (central half of the wide face).

Resin or bark pockets are gaps in the wood where the growing tree has captured some bark or resin. The bark or resin may still be there, but often it has disappeared leaving an empty dark-coloured pocket. All resin or bark pockets must have their width and length estimated. A piece is classed as within the grade where the pocket is smaller than the published size limit.

Sloping grain is one of the hardest characteristic to estimate. In some cases, the growth rings can distract from the actual slope of the grain. The grain is seen as very fine indentations in the wood.

Utility limits

Wane is usually seen as a missing corner, as the outside of the tree falls within the cross section. If more than the limiting percentage is missing, then the piece falls below the grade specification. Wane is caused by mechanical damage to the timber during processing.

Spring and bow are deformations in the unloaded timber. The grader must be able to estimate how far from being straight the piece is over the designated lengths.

Each species of timber listed in the visual grading standard has been tested (as small clear specimens) to find the strength of the wood fibre. This is used to assign a strength group to each species. Wood with stronger fibres has a higher strength group indicating its potential to deliver stronger pieces if there are not too many strength limiting characteristics.

The process of obtaining timber boards with estimated characteristic properties using visual grading as the 'sorting' method, is based upon the following processes:

- For the species being graded, the standard gives the strength group, which is used to link the structural grade of each group to the F-grade appropriate for that species.

- Within the species population, the sawn timber is sorted into various structural grades by the grader based on the presence of strength-limiting growth characteristics such as knots. They also check for utility limits as well.

- Each of these structural grades is assigned a strength or stress grade, (commonly referred to as its F-grade). The visual grading standards provide tables that link the structural grades for each species to a stress grade.

The following is an example of the use of visual grading rules to sort unseasoned tallowwood in a hardwood mill. (hardwood visual grading rules are different to the softwood visual grading rules):

Step 1: Unseasoned tallowwood has Strength Group S2 as given in the hardwood visual grading Standard AS 2082.

Step 2: The production of timber is sorted into structural grades as it comes out of the Green Mill. In reality, there will be at most 3 outputs, eg Structural Grade 3 and better, Structural Grade 4, and reject material.

Step 3: Because a single species, tallowwood, is being handled, it is possible to attach a single F-grade to each of the outputs. Structural Grade 3 and better will be given the stress grade F14. Structural Grade 4 will be given the stress grade F11. The reject material will not be given a stress grade. A grade stamp will be placed on each piece of F14 and F11 timber.

Note: for other species, different F-grades may be given to the same structural grades. Also, the stress grades awarded to seasoned timber will be different to the stress grades awarded to unseasoned timber of the same species.

For example, unseasoned (green) river red gum belongs to Strength Group S5. If a particular piece of river red gum meets the visual requirements for Structural Grade 1, the table below shows that it is assigned a stress grade of F11. Similarly, seasoned mountain ash belongs to Strength Group SD3 and when a particular piece meets the visual requirements for Structural Grade 1, it is assigned a stress grade of F27. The table below is taken from the visual grading standards AS 2082 and AS 2858, and illustrates the sorting system appropriate for use with visually graded timber. The classification of many species into strength groups can be found in AS 1720.2.

Table - Relationship between Strength Groups, Structural Grades and Stress Grades for most species

Strength | Stress Grade (assigned to each piece of timber) | ||||

Group (species property) | Structural Grade No. 1 (from VSG) | Structural Grade No. 2 (from VSG) | Structural Grade No. 3 (from VSG) | Structural Grade No. 4 (from VSG) | |

‑ | SD1 | ‑ | F34 | F27 | F22 |

‑ | SD2 | F34 | F27 | F22 | F17 |

S1 | SD3 | F27 | F22 | F17 | F14 |

S2 | SD4 | F22 | F17 | F14 | F11 |

S3 | SD5 | F17 | F14 | F11 | F8 |

S4 | SD6 | F14 | F11 | F8 | F7 |

S5 | SD7 | F11 | F8 | F7 | F5 |

S6 | SD8 | F8 | F7 | F5 | F4 |

S7 | ‑ | F7 | F5 | F4 | ‑ |

Note: This table is for guidance only. Some species (eg radiata pine) have special grade allocations.

Classification of a structural grade to an F-grade is given for common species in the visual stress-grading Standards. For less common species, AS 2878 can be used to assign a stress grade on the basis of small clear specimen data and strength reduction factors which allow for the effects of the naturally occurring characteristics mentioned earlier.

The relationship between clear wood strength and the various structural grades is shown in the following table:

Table - Relative strength of Structural Grades

Structural Grade: | % of clear wood strength |

No. 1 | 75% |

No. 2 | 60% |

No. 3 | 48% |

No. 4 | 38% |

No. 5 | 30% |

Visual stress-grading does not require verification of properties of graded material. It relies on relationships originally established in the USA for Douglas fir and modified to suit Australian species.

Strength tests on visually graded timber have shown that there is a lot of conservative overlap in strength range between the grades. Structural 3 Grade is the mid-level grade of structural timber and Structural 1 is the highest, however, testing of Structural 3 Grade shows that much more than half of the Structural 3 pieces tested were strong enough to have been sold as Structural 1 Grade.

The problem is that the visual grading process cannot identify those pieces. The overlap is conservative in that the majority of pieces within a grade have properties that are much stronger than those indicated for the marked grade.